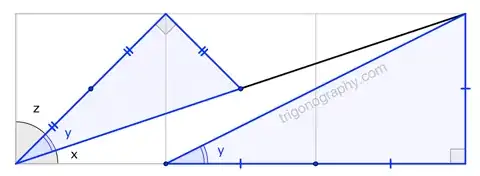

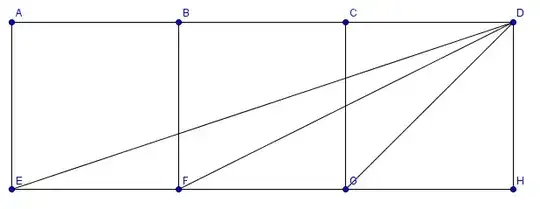

How can I show that $x+y=z$ in the figure without using trigonometry? I have tried to solve it with analytic geometry, but it doesn't work out for me.

- 6,718

- 161

- 1

- 1

- 7

-

Are all figures in the image intended to be squares? – Edward Jiang Jan 09 '16 at 20:00

-

Yes! I forgot to mention that. – Hamid Mohammad Jan 09 '16 at 20:01

-

4See the solution detailed here. It also comes with a nice extension problem which can be approached similarly. – πr8 Jan 09 '16 at 20:10

5 Answers

- 26,600

-

2

-

-

@FlybyNight: Compare the ratios of corresponding sides of $\angle G$ in both triangles. (This is effectively the product relation provided in Batominovski's answer.) – Blue Jan 09 '16 at 23:53

-

@Blue Hi Blue. My comment was aimed at wojowu, in the hope that s/he might add the detail to his/her original answer. – Fly by Night Jan 10 '16 at 00:13

Let $X$, $Y$, and $Z$ be the apexes of the angles $x$, $y$, and $z$, respectively. Also, let $P$ be the common intersection of the red lines. Show that $ZP^2=ZX\cdot ZY$. Thus, the circumcircle of the triangle $PXY$ is tangent to $PZ$ at $P$. This will prove that $\angle YPZ=\angle YXP=x$.

- 49,629

-

-

See the last proposition on http://staff.argyll.epsb.ca/jreed/math20p/circles/tangent.htm. – Batominovski Jan 09 '16 at 21:03

Equivalently, you have to prove that $$ \underbrace{\mathrm{arctan}(1/3)}_{x}+\underbrace{\mathrm{arctan}(1/2)}_{y}=\underbrace{\mathrm{arctan}(1)}_{z}. $$ This is pretty clear by addition of tangents, indeed $$ \tan(x+y)=\frac{\tan(x)+\tan(y)}{1-\tan(x)\tan(y)}=1 \implies x+y=\frac{\pi}{4}. $$

- 15,423

- 3

- 24

- 57

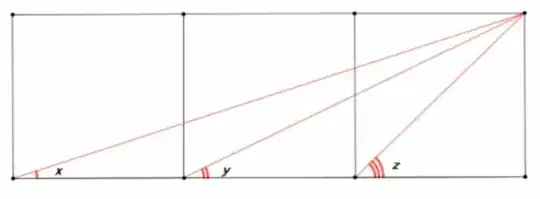

Imagine that all the the squares are 1 by 1 and so the rectangle has base 3 and a height of $1$.

There are three right-angled triangles in the diagram. The one with angle $x$ has base 3, and height 1. The triangle with angle $y$ has base 2 and height 1. The triangle with angle $z$ has base 1 and height 1.

Using the standard trig' ratio $\tan \theta = \frac{\mathrm{opp}}{\mathrm{adj}}$, we get $\tan x = \frac{1}{3}$, $\tan y = \frac{1}{2}$ and $\tan z= \frac{1}{1}=1$.

There is a well-know formula for angle addition:

$$\tan(\alpha+\beta) = \frac{\tan \alpha + \tan \beta}{1-\tan \alpha \tan \beta}$$

Applying this formula to the case of $\alpha =x$ and $\beta = y$ gives: $$\tan(x+y) = \frac{\tan x + \tan y}{1-\tan x \tan y}=\frac{\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{2}}{1-\frac{1}{3}\cdot\frac{1}{2}}=1$$ It follows that $\tan(x+y)=\tan z$. Since $0^{\circ} < x<y<z < 90^{\circ}$ it follows that $$\tan(x+y) = \tan z \iff x+y = z$$

- 32,272

-

-

@Blue All of the answers given so far involve trigonometry to some degree, even yours. The fact that you don't mention sine, cosine or tangent is irrelevant. The answer to the OP's question should be: no such answer exists. Trigonometry is the science of triangles using lengths, angles and their ratios. I could re-phrase my answer in terms of lengths and proprtion, but that's really just trigonometry, but without the nice simple place-holders of sine, cosine and tangent. – Fly by Night Jan 09 '16 at 22:40

-

If you use trigonometry for a question that asked for an answer without trig, than you are obligated to define all your terms and identitities. – fleablood Jan 09 '16 at 22:51

-

And you certainly can not simply say "there is a well known identity" unless you actually prove it. – fleablood Jan 09 '16 at 22:52

-

1@fleablood You're absolutely right. I hadn't read the "without trigonometry" until after I'd written my answer. However, being asked to solve this problem without trigonometry is, like I said, being asked to solve it without using angles, lengths, and their ratios. I'll leave my answer here because I think it might help people who Google this question in the future, and who are willing to use trigonometry to solve problems involving triangles. – Fly by Night Jan 09 '16 at 22:55

-

Technically speaking, everything we learn of similar triangles in geometry is a form of trig. But the student who hasn't study trig doesn't know what trig is. Blue's answer is accessible to a geometry student. Yours is not. – fleablood Jan 09 '16 at 23:09

-

@FlybyNight: As a self-styled "trigonographer", I certainly agree that trigonometry is the study of triangle measurements. (It's in the name!) So, sure, if we're being pedantic, a trig-less solution to an angle-sum problem is an impossibility. (In fact, I considered adding a disclaimer to this effect on my answer. :) That said, we reasonably read "without using trigonometry" as OP's hope to avoid sophisticated trigonometric machinery. My sol'n involves trig (as it must), but only at its most-fundamental level: identifying and exploiting similar triangles. sin/cos/tan stuff isn't necessary. – Blue Jan 09 '16 at 23:32

-

1

-

1@fleablood Be careful with the accessibility statement. We teach children trigonometry from the ages of 13/14 in the UK. The angle addition formulae come along at around 16/17. My answer is perfectly accessible for someone able to generate the graphic like the OP did. It's not like I'm using cohomology. – Fly by Night Jan 09 '16 at 23:45