CONTEXT

I was recently working on some Euclidean geometry problems that involved regular pentagons and triangles, such as this one, and this one (to which the current question specifically refers). I noted that sometimes I was "forced" to introduce a "dummy" point that I then proved being coincident with the point actually involved in the hypotheses. My quesiton is, therefore, if this procedure is really needed, and, if so, "why".

THE PROBLEM

Here is the problem statement, that, as mentioned, is part of this proof.

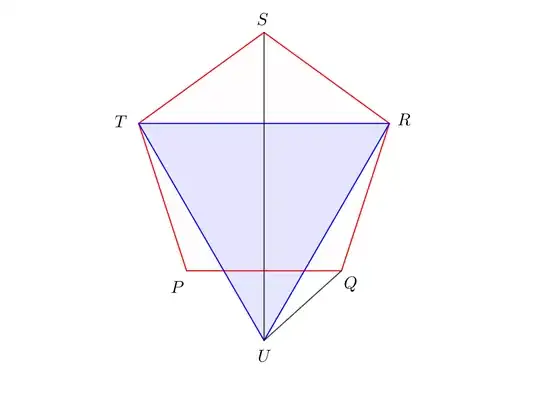

Let $PQRST$ be a regular pentagon, and let $U$ be a point on the perpendicular bisector of $PQ$, such that $\measuredangle PQU = 42^\circ$. Prove that $\triangle RTU$ is equilateral.

MY APPROACH

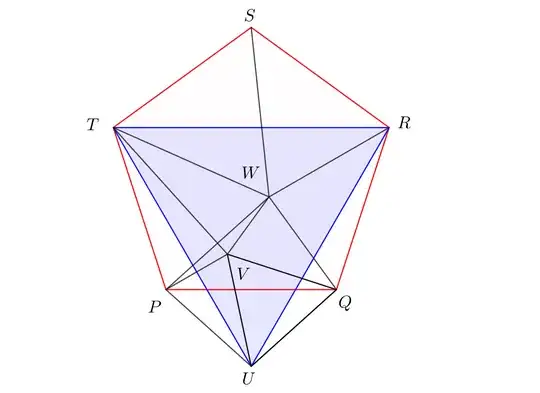

I solved the problem by introducing the equilateral triangle $\triangle RTU'$. Angle chasing and the fact that $\triangle TQU'$ is isosceles leads to the required result, that is $\measuredangle PQU' = 42^\circ$, and therefore $U'\equiv U$.

MY QUESTION

I would say I formally showed the reversed implication, i.e. that if the triangle is equilateral than $\measuredangle PQU = 42^\circ$. However, since there is only one point $U$ on the perpendicular bisector of $PQ$ with the property $\measuredangle PQU = 42^\circ$, then we can also state that the original assertion is true.

Is there a more direct approach, not involving the point $U'$? If not, does it make any sense to ask oneself why this is not possible? And, if so, what is the answer to this question?