I will use the shorthand $\zeta_n = \exp(2\pi\mathrm{i}/n)$.

Regarding correctness, you may need to explain why passing from $J^{-1}$

to $\lambda^{-1}$ does not change the number of preimages.

To that end, it should be mentioned explicitly that for a given

$w\in\mathbb{C}\setminus\{0,1\}$ the function $\tau\mapsto\lambda(\tau)-w$

has exactly one simple zero in the fundamental region you have described,

if appropriate care is taken with inclusion or exclusion of boundary points.

This is a specialty of $\lambda$, it is not implied by just mentioning the

fundamental region.

I do not know whether Ahlfors's text contains a proof of this, but

the evergreen reference

- Whittaker & Watson (1915), A Course of Modern Analysis, 2nd edition,

Merchant Books, ISBN 1-60386-121-1

has a nice proof of this at about page 474, based on a contour integral.

As for solving $\lambda(\tau)=w$, note that

$$\begin{align}

\lambda(\tau+1) = \lambda(\tau-1) &=

\frac{\lambda(\tau)}{\lambda(\tau)-1}

\\ \lambda\left(\frac{-1}{\tau}\right) &= 1-\lambda(\tau)

\end{align}$$

(I suppose that Ahlfors covers that.)

Now $\tau=\mathrm{i}$ is fixed by $\tau\mapsto\frac{-1}{\tau}$, therefore

$$\begin{align}

\lambda(\mathrm{i}) &=

\lambda\left(\frac{-1}{\mathrm{i}}\right) =

1-\lambda(\mathrm{i})

\\\therefore\quad

\lambda(\mathrm{i}) &= \frac{1}{2}

\\ \lambda(\mathrm{i}+1) &=

\frac{\lambda(\mathrm{i})}{\lambda(\mathrm{i})-1} = -1

\\ \lambda\left(\frac{\mathrm{i}+1}{2}\right) &=

\lambda\left(\frac{-1}{\mathrm{i}-1}\right) =

1 - \lambda(\mathrm{i}-1) = 2

\end{align}$$

Similarly, $\tau=\zeta_3$ is fixed by $\tau\mapsto\frac{-1}{\tau+1}$, therefore

$$\begin{align}

\lambda(\zeta_3) = \lambda\left(\frac{-1}{\zeta_3+1}\right) &=

1 - \lambda(\zeta_3+1) =

1 - \frac{\lambda(\zeta_3)}{\lambda(\zeta_3)-1} =

\frac{-1}{\lambda(\zeta_3) - 1}

\\\therefore\quad

\lambda(\zeta_3) \left(\lambda(\zeta_3)-1\right) + 1 &= 0

\tag{*}

\\\therefore\quad

\lambda(\zeta_3) \in\left\{\zeta_6, \zeta_{-6}\right\}

\end{align}$$

In a similar manner, we can find that $\lambda(\zeta_6)$

fulfills the same polynomial equation $(*)$. This is all we need.

However, in case you want to disambiguate $\lambda(\zeta_3)$

and $\lambda(\zeta_6)$, a useful approach is to work out that

$\Im\lambda(\tau)>0$ in the right half of $\lambda's$ fundamental domain

(where $\Re\tau>0$) and $\Im\lambda(\tau)<0$ in the left half.

I will omit that here and just remark that

$$\begin{align}

\lambda(\zeta_3) &= \zeta_{-6}

\\ \lambda(\zeta_6) &= \lambda\left(\frac{-1}{\zeta_3}\right) =

1 - \lambda(\zeta_3) = \zeta_6

\end{align}$$

as you have speculated.

It should be noted that the locations of the preimages are consistent

with the symmetries of $J(\tau)$ with respect to the full modular group:

$$J(\tau+1) = J(\tau) = J\left(\frac{-1}{\tau}\right)$$

The result is that $J(\tau)$ has a triple zero at every

$\tau=\frac{a\zeta_6+b}{c\zeta_6+d}$ with

$\begin{pmatrix}a&b\\c&d\end{pmatrix}\in\operatorname{SL}(2,\mathbb{Z})$,

and that $J(\tau)=1$ has a double root at every

$\tau=\frac{a\mathrm{i}+b}{c\mathrm{i}+d}$ with

$\begin{pmatrix}a&b\\c&d\end{pmatrix}\in\operatorname{SL}(2,\mathbb{Z})$.

Keeping in mind that $ad-bc=1$, you can rewrite those formulae for $\tau$ as

$$\begin{align}

\frac{a\mathrm{i}+b}{c\mathrm{i}+d} &=

\frac{ac+bd+\mathrm{i}}{c^2+d^2} =

\frac{u + \mathrm{i}}{N}

\\ &\quad\text{where}\quad

N,u\in\mathbb{Z};\quad N>0;\quad N\mid (u^2+1)

\\ \frac{a\zeta_6+b}{c\zeta_6+d} &=

\frac{ac+bc+bd+\zeta_6}{c^2+cd+d^2} =

\frac{u + \zeta_6}{N}

\\ &\quad\text{where}\quad

N,u\in\mathbb{Z};\quad N>0;\quad N\mid (u^2+u+1)

\end{align}$$

Conversely, it can be shown, essentially by an induction that traces the

steps of the extended euclidean algorithm, that for every choice of

$N,u\in\mathbb{Z}$ fulfilling the stated conditions, a suitable

$\begin{pmatrix}a&b\\c&d\end{pmatrix}\in\operatorname{SL}(2,\mathbb{Z})$

can be determined. I suspect that you are already satisfied with

the transform-based representation, so I just mention this as a sidenote.

Feel free to ask for additional details if you are interested and get stuck.

I cannot resist mentioning a couple of well-known connections.

Simple algebraic manipulations reveal that

the locations $\tau$ where $J(\tau)=0$ resp. $J(\tau)=1$

can as well be identified with the (simple) zeros of

the Eisenstein series

$$\begin{align}

g_2 &= -4 (e_1 e_2 + e_1 e_3 + e_2 e_3)

\\\text{resp.}\quad

g_3 &= 4 e_1 e_2 e_3

\end{align}$$

or of the corresponding normalized series

$\operatorname{E}_4$ resp. $\operatorname{E}_6$.

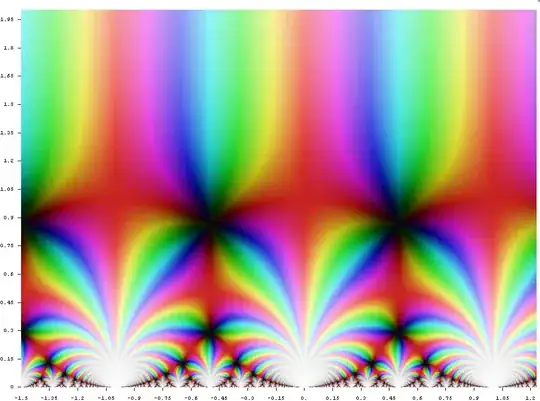

The zeros of $\operatorname{E}_6$ can also be recognized as the tangent points of the Ford circles, if you include the line $\Im\tau=1$ as an extra "circle".

To see that, note that both sets of points are invariant under

transformations of the full modular group, and coincede in the

full modular group's fundamental domain.