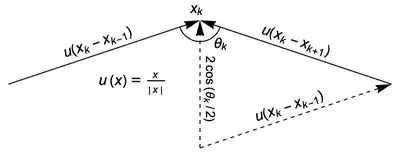

Unfortunately I do not know Convex Analysis too well, but here is one possible answer using Jensen's inequality. Each one of the sides of a polygon must be a chord of the circle, and each chord has an angle which corresponds to it.

Consider $n$ such angles, $\{\theta_1,\theta_2, \dots ,\theta_n\}; \sum_{k=1}^n \theta_k = 2\pi; \theta_i < \pi$ , which correspond with these chords, which form the perimeter of a polygon. It is not too hard to prove that the length of each chord is $2\sin(\theta_i/2)$.

The perimeter would be the sum of the chords:

$$2\sum_{k=1}^{n}\sin(\theta_k/2)=P$$

Since sine is concave from 0 to $\pi$, we may use the concave version of Jensen's:

$$f(\frac1n\sum_{k=1}^nx_i)\geq\frac1n\sum_{k=1}^nf(x_i)$$

$f(x)=2\sin(x/2), x_i=\theta_i$:

$$2\sin(\frac1{2n}\sum_{k=1}^n\theta_k))\geq\frac1n2\sum_{k=1}^{n}\sin(\theta_k/2)$$

$$P=2\sum_{k=1}^{n}\sin(\theta_k/2)\leq2n\sin(\frac1{2n}\sum_{k=1}^n\theta_k))$$

$\sum_{k=1}^n \theta_k = 2\pi$:

$$P=2\sum_{k=1}^{n}\sin(\theta_k/2)\leq2n\sin(\pi/n)$$

Now the current RHS is exactly what would happen if all of the $\theta_i$s were equal, and since every other case is lesser than that, we can see that the maximum possible perimeter is the regular polygon.

EDIT:

To prove that the length of the cord is $2 \sin(x/2)$ consider the following figure:

Where, given a circle of radius 1, we want to find the cord $CD$.

$AD=\cos(x)$, and so $DB=1-\cos(x)$.

$ABC$ is isosceles, so $\angle ACB=\angle ABC=\frac{\pi-x}2$

$\frac{DB}{\cos(\angle ABC)}=CB$, so substituting everything in, and using the double angle identity:

$$CB=\frac{1-\cos(x)}{\cos(\frac{\pi-x}2)}=\frac{1-(1-2\sin^2(x/2))}{\sin(x/2)}=\frac{2\sin^2(x/2)}{\sin(x/2)}=2\sin(x/2)$$