According to Approach0, this is new to MSE.

In classical logic, there is the notion of antecedent strengthening; namely:

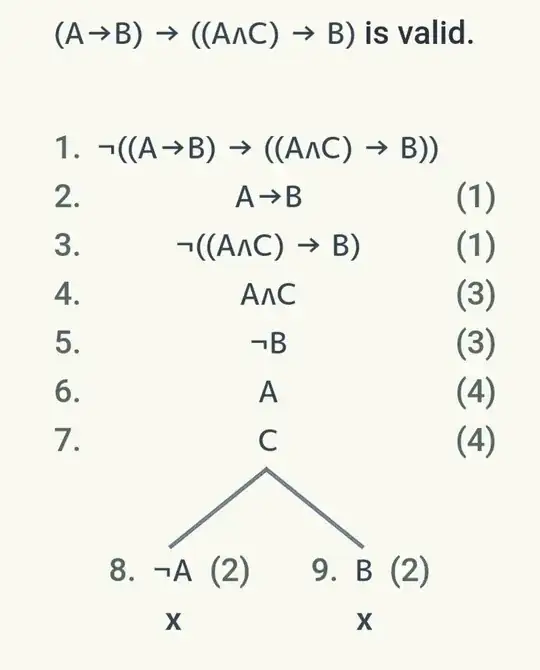

$$(A\to B)\to((A\land C)\to B)$$

is valid. A proof via tableau is given below.

It was generated here.

However, in a document on nonclassical logic (which can be found here), the following "counterexample" is given:

If Romney wins the election, he'll be sworn in in January. Therefore, if Romney wins the election and dies of a heart attack the same night, he'll be sworn in in January.

Here $A$ is "Romney wins the election", $B$ is "Romney will be sworn in in January", and $C$ is "Romney dies of a heart attack the same night as he wins the election".

My question is:

How does classical logic handle this supposed counterexample? What, if anything, is wrong with it?

I have a longstanding interest in nonclassical logics. See here for instance.

I doubt I could answer this myself. I don't want to end up a crank or anything, so I'm looking for an answer with full proofs or at least references.

I hope I have provided enough context.

Please help :)