Odometers

Up to some variations, an odometer is the topological dynamical system whose state space is $\mathbb{Z}_2$, the set of $2$-adic integers, and transformation is $T(x) = x+1$.

If you have never seen this before: $\mathbb{Z}_2$ is the completion of $\mathbb{Z}$ for the distance $d(x,y) = 2^{-\max \{n: 2^n | x \wedge 2^n | y\}}$. It is a compact topological group.

In practice, you can see an element of $\mathbb{Z}_2$ as a non-terminating (on the left) binary number $\ldots 010011$, where two numbers are added in the usual way (with carry to the left). For instance, $\ldots 010011+1 = \ldots 010100$. Topologically, it is homeomorphic to $\{0,1\}^\mathbb{N}$. Sometimes you may also see them represented by binary decimal numbers, such as $0.110010 \ldots$, but with carry to the right. For instance, $0.110010 \ldots+0.1 = 0.001010 \ldots$.

As a compact topological group, $\mathbb{Z}_2$ admits a unique translation-invariant probability measure, its Haar measure $\mu_H$. Its distribution is the same as choosing all binary digits independently, $0$ or $1$ with probability $1/2$.

It turns out that $(\mathbb{Z}_2, T)$ is uniquely ergodic, its unique invariant probability measure being the Haar measure.

Tilings

What does this has to do with tilings? Well, let's consider tilings on $\mathbb{Z}$. There are only two tilings of $\mathbb{Z}$ with tiles of length $2$: the one with endpoints on even integers, and the one with endpoints on odd integers.

There are four tilings of $\mathbb{Z}$ with tiles of length $4$. However, if we are given a tiling by tiles of length $2$, only two of them are compatible. For instance, if we are given the even tiling of length $2$, then the compatible tilings of length $4$ are those whose endpoints are $0[4]$, or those whose endpoints are $2[4]$.

It's the same with tilings of length $8$: there are eight of them, but only two of them are compatible with any tiling of length $4$.

Let $X$ be the set of sequences of tilings $(T_2, T_4, T_8, \ldots)$, where $T_{2^n}$ is a tiling by tiles of length $2^n$, and they are all compatible. Then, when refining the tiling, we have two choices at each step, so this set can be easily made in bijection with $\{0,1\}^{\mathbb{N}}$.

For a specific bijection, for $n \geq 1$, let $u_n$ be the smallest nonnegative value of an endpoint of a tile of length $2^n$, put $u_0 := 0$, and let:

$$x_n = \left\{ \begin{array}{lll} 1 & \text{ if } & u_n = u_{n-1} \\ 0 & \text{ if } & u_n > u_{n-1} \end{array}\right.,$$

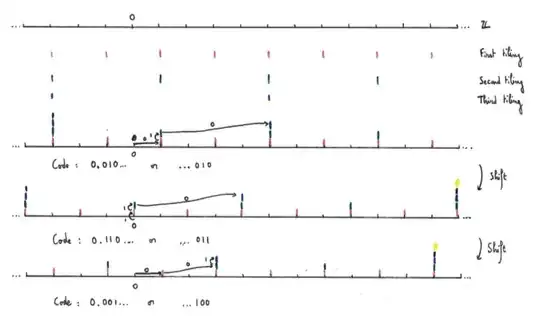

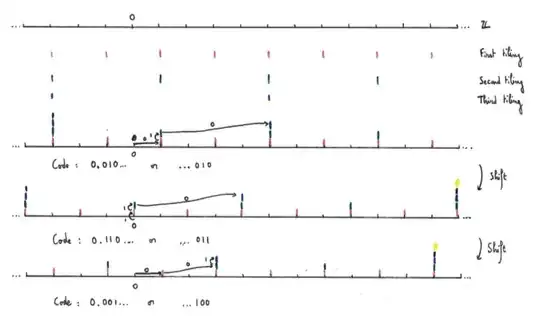

Then take $x := \ldots x_3 x_2 x_1 \in \mathbb{Z}_2$. For instance, $x = \ldots 010$ means that the $2$-tiles end on odd values, the $4$-tiles on $1[4]$ values, and the $8$-tiles on $5[8]$ values.

This yields a bijection $\varphi : X \to \mathbb{Z}_2$. The nice thing is that its conjugates the translation by $+1$ on $\mathbb{Z}$ (or rather, the translation $\widetilde{T}$ of $-1$ of the tilings) with $T$:

$$\varphi \circ \widetilde{T} = T \circ \varphi.$$

This gives you a geometric interpretation of the odometer as sequences of tilings. As a corollary, $X$ carries a unique translation-invariant probability measure.

Here is an example of tiling, its coding and the effect of the shift:

The construction

Now, $\mathbb{Z}^2$ acts on $\mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2$ by direct product: $(n,m) \cdot (x,y) = (T^n (x), T^m (y))$. But $\mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2$ can be seen as tilings of $\mathbb{Z}^2$ by squares (or rather, as compatible sequences of tilings by squares of side $2^n$); then $\mathbb{Z}^2$ acts merely by translation.

The set they construct is $\Omega \subset \mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2 \times \{\pm 1\}^{\mathbb{Z}^2} \simeq X \times X \times \{\pm 1\}^{\mathbb{Z}^2}$, corresponding to markings compatible with both tilings (i.e. triples $(x,y,z) \in X^2 \times \{\pm 1\}^{\mathbb{Z}^2}$ where $z$ satisfies a condition based on $x$ and $y$).

As for the measure: the only $\mathbb{Z}^2$-invariant measure on $X^2$ is $\varphi^* \mu_H \otimes \varphi^*\mu_H$. Then, given $(x,y) \in X^2$, the authors describe a measure on the set of good markings

$C(x,y) \subset \{ \pm 1 \}^{\mathbb{Z}^2}$. This is the distribution $\nu_{x,y}$ of $z$ conditionally to $(x,y)$. The total measure is (abusing notation and writing $\mu_H$ for $\varphi^* \mu_H$):

$$\mu := \iint \delta_x \otimes \delta_y \otimes \nu_{x,y} \ d \mu_H (x) \ d \mu_H (y).$$

Let us look closer at this step. Fix $x$ and $y$, that is, fix a sequences of tilings of $\mathbb{Z}^2$. Let $\sim$ be the equivalence relation on $\mathbb{Z}^2$ generated by the tiling and the prescribed rule. That is, if $\{(a,b), (a+1, b), (a, b+1), (a+1,b+1)\}$ is a $2\times 2$ tile, then $(a,b) \sim (a, b+1)$ and $(a+1,b) \sim (a+1, b+1)$, etc.

Then we have countably any equivalence classes $(\alpha_n)_{n \geq 0}$ on $\mathbb{Z}^2$. Let $(X_n)_{n \geq 0}$ be i.i.d., with value $\pm 1$ with probability $1/2$. Finally, let $Y (a,b) := X_n$ whenever $(a,b) \in \alpha_n$. Then, by construction, $(Y(a,b))_{(a,b) \in \mathbb{Z}^2} \in C(x,y)$, and $\nu_{x,y}$ is its distribution.

The statement that "one sees independent random variables along the $45°$ diagonal" comes from the fact that, on any $45°$ diagonal, all the cells belong to different equivalence classes, so the corresponding $Y(a,b)$ are independent.