Let's be clear: continuity and differentiability begin as a concept at a point. That is, we talk about a function being:

- Defined at a point $a$;

- Continuous at a point $a$;

- Differentiable at a point $a$;

- Continuously differentiable at a point $a$;

- Twice differentiable at a point $a$;

- Continuously twice differentiable at a point $a$;

and so on, until we get to "analytic at the point $a$" after infinitely many steps.

I'll concentrate on the first three and you can ignore the rest; I'm just putting it in a slightly larger context.

A function is defined at $a$ if it has a value at $a$. Not every function is defined everywhere: $f(x) = \frac{1}{x}$ is not defined at $0$, $g(x)=\sqrt{x}$ is not defined at negative numbers, etc. Before we can talk about how the function behaves at a point, we need the function to be defined at the point.

Now, let us say that the function is defined at $a$. The intuitive notion we want to refer to when we talk about the function being "continuous at $a$" is that the graph does not have any holes, breaks, or jumps at $a$. Now, this is intuitive, and as such it makes it very hard to actually check or test functions, especially when we don't have their graphs. So we need a definition that is mathematical, and that allows for testing and falsification. One such definition, apt for functions of real numbers, is:

We say that $f$ is continuous at $a$ if and only if three things happens:

- $f$ is defined at $a$; and

- $f$ has a limit as $x$ approaches $a$; and

- $\lim\limits_{x\to a}f(x) = f(a)$.

The first condition guarantees that there are no holes in the graph; the second condition guarantees that there are no jumps at $a$; and the third condition that there are no breaks (e.g., taking a horizontal line and shifting a single point one unit up would be what I call a "break").

Once we have this condition, we can actually test functions. It will turn out that everything we think should be "continuous at $a$" actually is according to this definition, but there are also functions that might seem like they ought not to be "continuous at $a$" under this definition but are. For example, the function

$$f(x) = \left\{\begin{array}{ll}

0 & \text{if }x\text{ is a rational number,}\\

x & \text{if }x\text{ is not a rational number.}

\end{array}\right.$$

turns out to be continuous at $a=0$ under the definition above, even though it has lots and lots of jumps and breaks. (In fact, it is continuous only at $0$, and nowhere else).

Well, too bad. The definition is clear, powerful, usable, and captures the notion of continuity, so we'll just have to let a few undesirables into the club if that's the price for having it.

We say a function is continuous (as opposed to "continuous at $a$") if it is continuous at every point where it is defined. We say a function is continuous everywhere if it is continuous at each and every point (in particular, it has to be defined everywhere). This is perhaps unfortunate terminology: for instance, $f(x) = \frac{1}{x}$ is not continuous at $0$ (it is not defined at $0$), but it is a continuous function (it is continuous at every point where it is defined), but not continuous everywhere (not continuous at $0$). Well, language is not always logical, we just learn to live with it (witness "flammable" and "inflammable", which mean the same thing).

Now, what about differentiability at $a$? We say a function is differentiable at $a$ if the graph has a well-defined tangent at the point $(a,f(a))$ that is not vertical. What is a tangent? A tangent is a line that affords the best possible linear approximation to the function, in such a way that the relative error goes to $0$. That's a mouthful, you can see this explained in more detail here and here. We exclude vertical tangents because the derivative is actually the slope of the tangent at the point, and vertical lines have no slope.

Turns out that, intuitively, in order for there to be a tangent at the point, we need the graph to have no holes, no jumps, no breaks, and no sharp corners or "vertical segments".

From that intuitive notion, it should be clear that in order to be differentiable at $a$ the function has to be continuous at $a$ (to satisfy the "no holes, no jumps, no breaks"), but it needs more than that. The example of $f(x) = |x|$ is a function that is continuous at $x=0$, but has a sharp corner there; that sharp corner means that you don't have a well-defined tangent at $x=0$. You might think the line $y=0$ is the tangent there, but it turns out that it does not satisfy the condition of being a good approximation to the function, so it's not actually the tangent. There is no tangent at $x=0$.

To formalize this we end up using limits: the function has a non-vertical tangent at the point $a$ if and only if

$$\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(a+h)-f(a)}{h}\text{ exists}.$$

What this does is just saying "there is a line that affords the best linear approximation with a relative error going to $0$." Once you check, it turns out it does capture what we had above in the sense that every function that we think should be differentiable (have a nonvertical tangent) at $a$ will be differentiable under this definition. Again, turns out that it does open the door of the club for functions that might seem like they ought not to be differentiable but are. Again, that's the price of doing business.

A function is differentiable if it is differentiable at each point of its domain. It is differentiable everywhere if it is differentiable at every point (in particular, $f$ is defined at every point).

Because of the definitions, continuity is a prerequisite for differentiability, but it is not enough. A function may be continuous at $a$, but not differentiable at $a$.

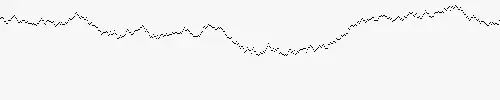

In fact, functions can get very wild. In the late 19th century, it was shown that you can have functions that are continuous everywhere, but that do not have a derivative anywhere (they are "really spiky" functions).

Hope that helps a bit.

Added. You ask about $|x|$ and specifically, about considering

$$\frac{|x+a|-|x-a|}{a}$$

as $a\to 0$.

I'll first note that you actually want to consider

$$\frac{f(x+a)-f(x-a)}{2a}$$

rather than over $a$. To see this, consider the simple example of the function $y=x$, where we want the derivative to be $1$ at every point. If we consider the quotient you give, we get $2$ instead:

$$\frac{f(x+a)-f(x-a)}{a} = \frac{(x+a)-(x-a)}{a} = \frac{2a}{a} = 2.$$

You really want to divide by $2a$, because that's the distance between the points $x+a$ and $x-a$.

The problem is that this is not always a good way of finding the tangent; if there is a well-defined tangent, then the difference

$$\frac{f(x+a)-f(x-a)}{2a}$$

will give the correct answer. However, it turns out that there are situations where this gives you an answer, but not the right answer because there is no tangent.

Again: the tangent is defined to be the unique line, if one exists, in which the relative error goes to $0$. The only possible candidate for a tangent at $0$ for $f(x) = |x|$ is the line $y=0$, so the question is why this is not the tangent; the answer is that the relative error does not go to $0$. That is, the ratio between how big the error is if you use the line $y=0$ instead of the function (which is the value $|x|-0$) and the size of the input (how far we are from $0$, which is $x$) is always $1$ when $x\gt 0$,

$$\frac{|x|-0}{x} = \frac{x}{x} = 1\quad\text{if }x\gt 0,$$

and is always $-1$ when $x\lt 0$:

$$\frac{|x|-0}{x} = \frac{-x}{x} = -1\quad\text{if }x\lt 0.$$

That is: this line is not a good approximation to the graph of the function near $0$: even as you get closer and closer and closer to $0$, if you use $y=0$ as an approximation your error continues to be large relative to the input: it's not getting better and better relative to the size of the input. But the tangent is supposed to make the error get smaller and smaller relative to how far we are from $0$ as we get closer and closer to zero. That is, if we use the line $y=mx$, then it must be the case that

$$\frac{f(x) - mx}{x}$$

approaches $0$ as $x$ approaches $0$ in order to say that $y=mx$ is "the tangent to the graph of $y=f(x)$ at $x=0$". This is not the case for any value of $m$ when $f(x)=|x|$, so $f(x)=|x|$ does not have a tangent at $0$. The "symmetric difference" that you are using is hiding the fact that the graph of $y=f(x)$ does not flatten out as we approach $0$, even though the line you are using is horizontal all the time. Geometrically, the graph does not get closer and closer to the line as you approach $0$: it's always a pretty bad error.