I can see why you are confused as his writing presumes a little more design savviness on the part of the reader, and so is a little handwavy.

Responsibilities are dependent on the domain and on how software evolves ("reason to change", not as imagined solely by the developer, but as established (possibly over time) by business needs - by the outside forces that drive changes in the codebase). To create maintainable code, you (and your team) have to figure these out and structure your software over time to support those kinds of changes. (Note that initially, doing design doesn't pay off in an obvious way, which is why it's not easy for less experienced developers to see its utility; on top of that there is risk of "overdesign". But later on, if you don't consider it, you get in trouble.)

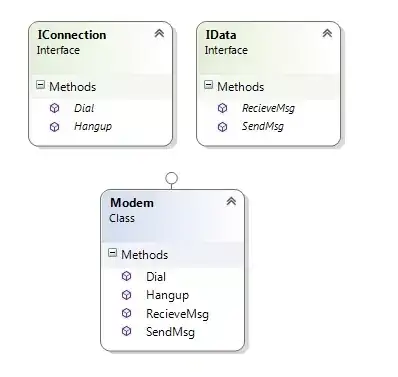

So he starts with the assumption that it has somehow been established that connection management and data communication are two distinct responsibilities - in the sense that when you look at the change requests they generally don't change together.

Then he talks about the responsibilities of the interface itself - which you could read as different reasons for the interface to change. This is of interest, because, even though it has no implementation, it's a static peace of code that other code depends on. One of the major concerns in design is controlling the directions and the structure of dependencies, because changes propagate backwards along dependency arrows (which is why DIP is a technique to stop that propagation - it reverses the arrow at some point).

He doesn't say much about how separating the interface allows you to achieve (or rather, increase) independent evolvability of the client code that calls the two interfaces. But if I had to fill in the blanks: this relies on the discipline and design knowledge of the developers, in the sense that they can now, in client code, leverage this to separate the "orchestration" of these calls (the "orchestration", the logic of what is called and when - being the responsibility of the clients). This may be as simple as two different client classes, or something more involved, where the clients reside in separate DLLs. On top of that, clients do not know if the interface is implemented by a single class, or two separate classes, or a whole subsystem. So that gives you flexibility to change the implementation behind the interface.

He also says, and this is important, if these two don't change separately (either because they don't change at all, or because their changes are strongly correlated), you shouldn't apply SRP or ISP just for the sake of it.

An axis of change is an axis of change only if the changes occur. It

is not wise to apply SRP or any other principle, for that matter if

there is no symptom.

So, you don't do design once - yes, you come up with something initially, but you develop it and reconsider it over time.

As for the SRP violation in the implementation - in the paragraph just below the text you've read so far, he acknowledges that, and writes:

Note that [...] I kept both responsibilities coupled in the

ModemImplementation class. This is not desirable, but it may be

necessary. There are often reasons, having to do with the details of

the hardware or operating system, that force us to couple things that

we'd rather not couple. However, by separating their interfaces, we

have decoupled the concepts as far as the rest of the application is

concerned.

We may view the ModemImplementation class as a kludge or a wart;

however, note that all dependencies flow away from it. Nobody needs to

depend on this class. Nobody except main needs to know that it exists.

Thus, we've put the ugly bit behind a fence. Its ugliness need not

leak out and pollute the rest of the application.

So there's a fair bit of depth to it - understanding the domain, understanding practical considerations, understanding trade-offs, etc.

ModemImplclass does indeed implement the methods individually. – Kache Mar 03 '19 at 16:36