By about 1640, the solution to the "area problem" for curves with equation $Y^n = aX^m$ was known by Fermat for all integer cases except when $n = 1, m = -1$.

I.e., the only unsolved area problem was for $Y = \frac 1X$ - the standard equation for the graph of a hyperbola.

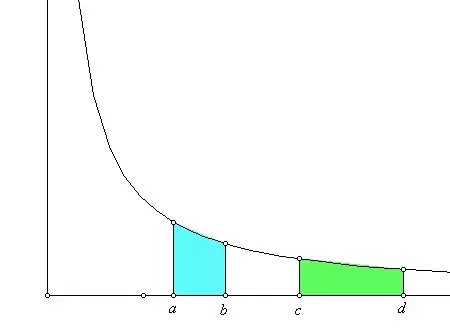

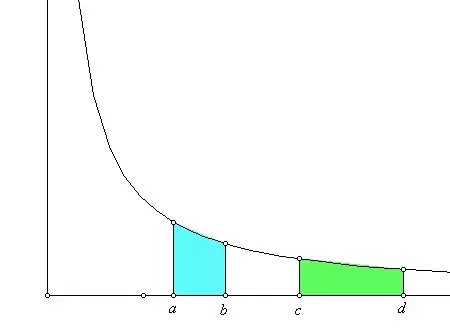

In 1647, Gregoire de St. Vincent showed the following special property for hyperbolas:

If: $\frac ab = \frac cd$ then $\int_a^b\frac 1x dx=\int_c^d\frac 1x dx$

In 1649 Alfonso Antonio de Sarasa recognized this feature in Gregoire's work and connected it to the properties of logarithms. In particular he recognized the following additive property of these measurements which had previously be a key feature in the study of common logarithms (base 10): the area determined by a product of two numbers , bd, is equal to the sum of the areas determined by b and d separately.

If $\frac ab = \frac cd$ and $a=1$ and $c=1$ then $\frac 1b \not= \frac 1d$, but $\frac 1b + \frac 1d = \frac {1}{bd}$

This is the same as saying what RGB did:

$$\int_{1}^{bd}\frac{\text{d}t}{t}=\int_{1}^{b}\frac{\text{d}t}{t}+\int_{1}^{d}\frac{\text{d}t}{t}$$

$$f(bd)=f(b)+f(d)$$

$$ A^b A^d=A^{b+d}$$

Thus a logarithmic relationship was implied and A was found to be e.

$$ \int_1^b \frac 1x dx = \ln(b)$$

$$ \int_1^d \frac 1x dx = \ln(d)$$

$$ \int_1^{bd} \frac 1x dx = \ln(b)+\ln(d)$$

Source

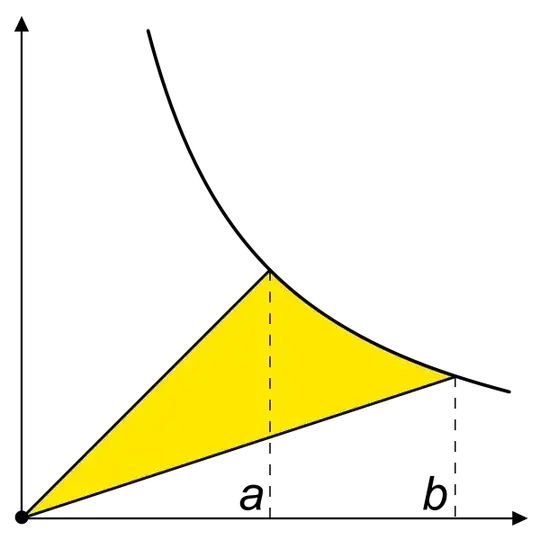

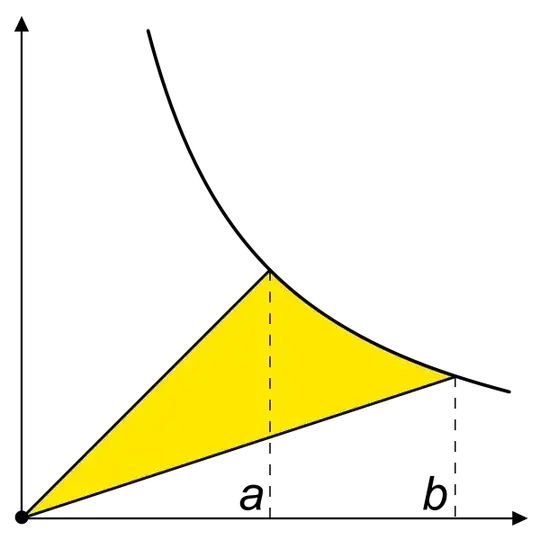

The Hyperbolic Angle "$u$" is defined in relation to the function $\frac 1x$:

The magnitude of the hyperbolic angle "$u$" is the area of the corresponding hyperbolic sector (red above, yellow below) which is ln x since it is defined as the integral of the projection onto the axis from a=1 or y=x to b: $\int_1^b \frac 1x dx=\ln(b)$

While power series were not involved in the discovery of the natural logarithm, they can be used to show the relationship between $\frac 1x$ and e:

If a function is its own derivative then: $ y=f(x), \frac{dy}{dx}=y$

Such a function is a series: $ y=1+x+\frac{x^2}{2!}+\frac{x^3}{3!}+\dots$

$$\frac{dy}{dx}=0+1+\frac{2x}{2!}+\frac{3x^2}{3!}+\frac{4x^3}{4!}\dots=1+x+\frac{x^2}{2!}+\frac{x^3}{3!}+ \dots$$

If we differentiate $y^p$: $ \frac{d(y^p)}{dx}=py^{p-1}\frac{dy}{dx}$

Since $ \frac{dy}{dx}=y$ it follows: $ \frac{d(y^p)}{dx}=py^{p-1}y=py^p$

Given: $y_1=1+z+\frac{(z)^2}{2!}+ \frac{(z)^3}{3!}+\dots$

$$\frac{dy_1}{dz}= 1+z+\frac{(z)^2}{2!}+ \frac{(z)^3}{3!}+\dots=y_1$$

Let $z=ax$,$\frac{dy_1}{d(ax)}=y_1$ $\frac{dy_1}{d(x)}=ay_1$

$$y_1=y^p= 1+px+\frac{(px)^2}{2!}+ \frac{(px)^3}{3!}+\dots=y_1$$

If we let $p=\frac 1x$ then, $y^{\frac 1x}=1+1+\frac{(1)^2}{2!}+ \frac{(1)^3}{3!}+\dots=e$

And Hence replacing $e^1$ with $e^x$ yeilds:

$e^x=1+x+\frac{(x)^2}{2!}+ \frac{(x)^3}{3!}+\dots$

This all lead to the development of the Slide Rule as well as hyperbolic trig functions.