Throughout this post I'm assuming that the cone is pointing "up" in the $Z$ axis.

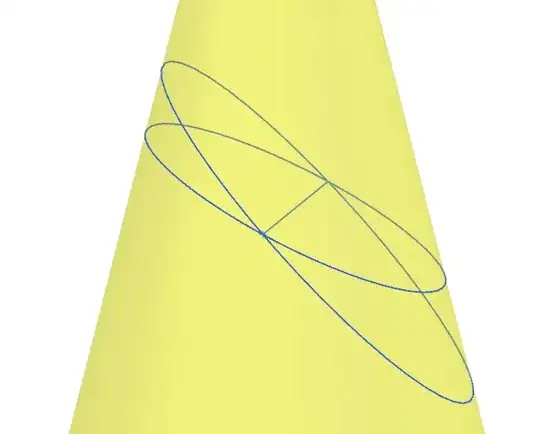

It's known that the intersection of a plane and cone is an ellipse. But what about the projection of this ellipse onto the $X,Y$ plane - is it always a circle? Or equivalently, does every intersection of a plane and cone lie in some cylinder pointing in the $Z$ direction? It is true for a plane and paraloboid intersection, but it doesn't seem like it for a cone plane intersection:

For a cone $z^2 = x^2 + y^2$ and a plane $z=\frac{x+1}{2}$ we have

$4 x^2 + 4 y^2 = 4z^2 = x^2 + 2x + 1$

$3x^2 -2x =-4y^2 + 1$

$x^2 - \frac{2}{3}x = \frac{-4}{3}y^2 + \frac{1}{3}$

$(x- \frac{1}{3})^2 - \frac{1}{9} = \frac{-4}{3}y^2 + \frac{1}{3}$

$(x- \frac{1}{3})^2 + \frac{4}{3}y^2 = \frac{4}{9}$

Which is not the equation for a circle.

Is there perhaps a cleaner way of showing that the projection of a plane and cone is not always a circle?