I was curious -- I know that all the elements of S are unique because gcd(a,p) = 1, but I was wondering -- What would be an example in which the elements were not unique?

Well, one where $p$ isn't prime and if $\gcd(a,p) \ne 1$ then you'd have $\frac p{\gcd(a,p)}$ distinct terms and the repeated $a$ times (minus a final term).

Example $a = 3$ and $p=24$ then $a\cdot 1,a\cdot 2, ......, a\cdot (p-1)\equiv 3,6,9,12,15,18,21,0,3,6,9,12,15,18,21,0,3,6,9,12,15,18,21$

what happened to the a? it just disappeared

Not quite

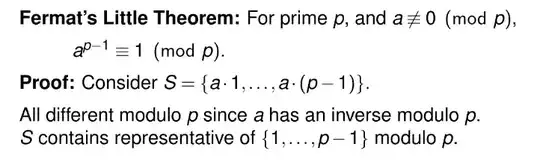

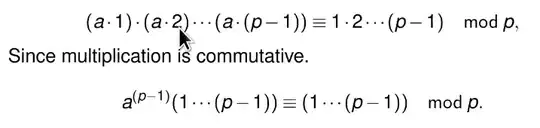

$a, a\cdot 2, a\cdot 3,...., a\cdot (p-1)$ represents a residue system (without $0$) in no particular order. And $1,2,3,......, p-1$ represent a residue system (without $0$). So each $a\cdot j \equiv k_j \pmod p$ for some $0\le k_j \le p-i$.

So $a\cdot a(2)a(3)......a(p-1)\equiv k_1k_2k_3.....k_{p-1}\pmod p$.

And $\{k_1,k_2,k_3,......k_{p-1}\} = \{1,2,3,....,(p-1)\}$ but not in any particular order.

So $k_1k_2k_3.....k_{p-1} = 1\cdot 2\cdot 3.....(p-1)$ because multiplication is commutative and we can put them in numeric order.

Here's an example:

$3^6 \equiv 1 \pmod 7$ because

$S = \{3,6,9,12,15,18\}$ contains a representative of each class $1....,6$. $1\equiv 15;2\equiv 9,3\equiv 3;4\equiv 18;5\equiv 12; 6\equiv 6$.

$3^6\cdot (1\cdot 2\cdot 3\cdot 4\cdot 5\cdot 6) =$

$3\cdot 6\cdot 9\cdot 12\cdot 15\cdot 18 \equiv $

$3\cdot 6 \cdot 2\cdot 5\cdot 1\cdot 4 \pmod 7\equiv$ (note those are not in any particular order)

$1\cdot 2\cdot 3\cdot 4\cdot 5\cdot 6 \pmod 7$ (but now we just rearranged them into order)

So $3^6(1\cdot ....\cdot 6) \equiv (1\cdot ....\cdot 6)\pmod 7$.

And.... $1\cdot ....\cdot 6$ is relatively prime to $7$ so it is invertible. (Actually be Wilson's Th it is congruent to $-1 \pmod 7$ but ... we don't need to know that.)

$3^6[(1\cdot ....\cdot 6)]((1\cdot ....\cdot 6)^{-1}\equiv (1\cdot ....\cdot 6)(1\cdot ....\cdot 6)^{-1}\pmod 7$ so

So $3^6 \equiv 1\pmod 7$.