We can adapt a standard trick used to solve the analogous problem for which we do not restrict to finite regions.

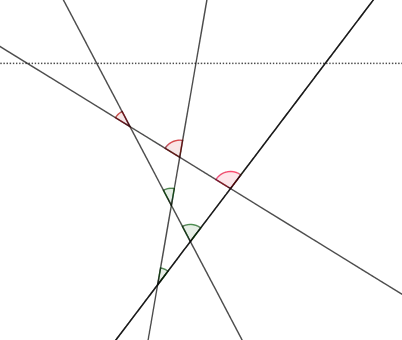

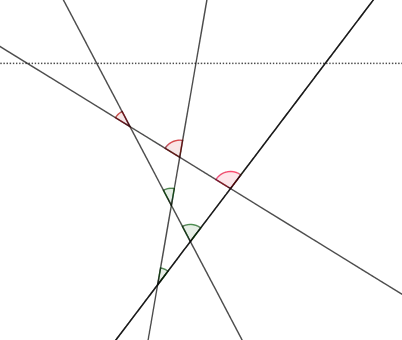

First, for any configuration of lines (like that of the solid lines in the diagram below), by rotating slightly we can assume that none of the lines are horizontal. Any region not bounded below has a unique lowest vertex (such regions may still be unbounded above), and conversely, every vertex is the lowest vertex of one region; in the diagram, the marked angles indicate which region is associated to each vertex.

The number of intersections---and hence the number of regions bounded below---is at most ${n \choose 2} = \frac{1}{2} n (n - 1)$, and this number is achieved exactly when the lines are in general position (i.e., no two lines are parallel, and no three lines intersect in a point). If we draw a horizontal line above all of the intersections (like the dotted line in the diagram), it intersects all $n$ of the lines in the original configuration (again, since none of those lines are horizontal), and so there are $n - 1$ regions corresponding to a vertex and unbounded above. (In the diagram, these are the regions marked by red angles.) Since every unbounded region is unbounded above or unbounded below, the maximum number of bounded regions is $$\frac{1}{2} n (n - 1) - (n - 1) = \color{#df0000}{\boxed{\frac{1}{2} (n - 1) (n - 2) = {n - 1 \choose 2}}} .$$ A standard induction argument shows this quantity value coincides with the term $x_n$ of your sequence for every $n$.

(Alternatively, if you take as given the result that $n$ lines in general position divide the plane into ${n + 1}\choose 2$ regions (including unbounded regions), then since $n$ lines yield $2 n$ unbounded regions---to see this, draw a circle enclosing all of the intersections of the lines---there are ${{n + 1}\choose 2} - 2 n$ bounded regions.)