The problem:

Defining $\sin x$ as the leg $b$ of a right triangle with $\angle B=x$ (in radians) and hypotenuse $1$, prove that $$\lim_{x\to 0}\frac{\sin x}x=1$$

(The motivation is to find the derivative of $\sin x$ in a elementary, "pre-Taylor" and "pre-series" context).

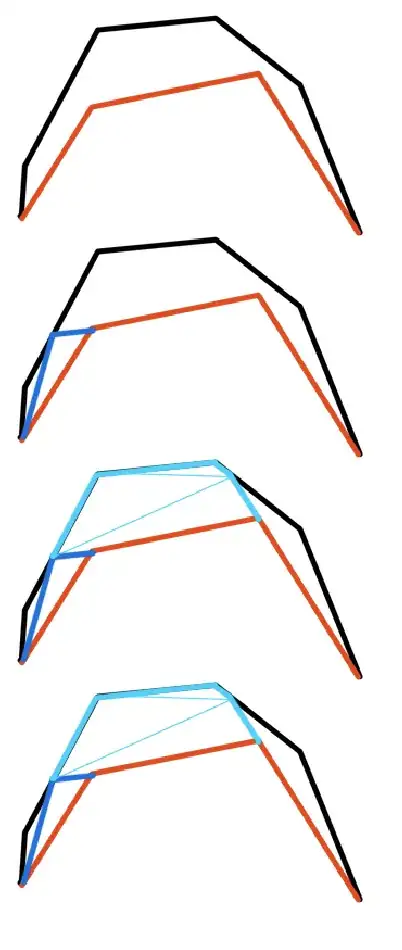

I have seen many times a proof that it is based in the fact that the length of the arc $x$ satisfies $$\sin x<x<\tan x$$ or sometimes $$\sin x<x<\sin x+1-\cos x$$ The lower bound is clear because the $\sin x$ is the length of a straight segment and $x$ is the length of a curved segment with the same endpoints. But I find that the upper bound is based on this intuitive fact:

If $F$ and $G$ are two convex subsets of $\Bbb R^2$ and $F\subset G$, then $|\partial F|<|\partial G|$.

($|\partial F|$ is the length of the boundary of $F$).

But I haven't ever seen a proof of that. I tried it myself but I get stuck trying to bound $$\int_s^t\sqrt{1+y'(u)^2}du$$ provided for example that $y''$ is negative and $y(s)=y(t)$. I realize that $y'$ can't be bounded (note for example $y=\sqrt{1-x^2}$, $-1\le x\le 1$).

Question

Is it possible to justify the derivative of $\sin x$ or the inequality about the lengths of bounds? Is there any calculus text with this approach (or similar) to define trigonometical functions?