I hope this question is not too long, but I have included some extra information to clarify the context of the question and hopefully avoid the 'circular' arguments which inevitably occur on this topic (please pardon the unavoidable pun).

In this question, by "proving $\pi$ exists" I mean proving that the limit of the following sequence $(p_{n})$ of real numbers exists, according to the familiar formal definition of sequence convergence from analysis, ie $\exists L \in \mathbb{R}$ such that $\forall \varepsilon > 0, \exists N$ such that $\forall n > N, | p_{n} - L | < \varepsilon $ :-

Firstly define $C_{n} =$ perimeter of the $n$-sided regular polygon inscribed inside the circle of radius $r$, so that (by elementary means) we have $C_{n} = 2r(n \sin \frac{SA}{n})$, and then define $p_{n} = n \sin \frac{SA}{n}$, so that $C_{n} = 2rp_{n}$, where $S\!A$ denotes a 'straight-angle'.

By "without formal analysis" I mean with only the most basic notions of limits from analysis - ie just enough for us to have a formal definition of a limit and its most basic properties (such as adding/multiplying limits and the Cauchy criteria for convergence).

Please note I have not used any angle measure in the above definition of $p_{n}$ to emphasize that the question is at the very elementary level of Geometry - with only the most basic ideas of limiting processes being used, ie. the formal definition of convergence of a sequence in $\mathbb{R}$, the basic properties of sums and products of such limits, and the Cauchy criteria for convergence (all of which are established at very early stage in real analysis). The elementary Geometry comprises the basic notions such as found in Euclid's Elements, concerning primarily straight lines and flat surfaces, but not curved objects - except for the circle, which we are just starting to consider in regard to $\pi$. This very basic Euclidean Geometry includes such things as the similar triangles, trigonometric ratios and their formulae, and lengths and areas of straight lines and polygonal regions, properties of angles in circles, and the Pythagorean Identity, and so on. It also includes $\mathbb{R}$ defined geometrically as a continuum of points using the real number line (ie 1D Euclidean Space), which is a Complete Ordered Field, containing the rational sub-field $\mathbb{Q}$. (As any two Complete Ordered Fields must be order isomorphic, analysis thus applies to this geometric 'version' of $\mathbb{R}$). This basic geometry suffices to obtain the formula for $C_{n}$ above. It does not use limiting processes except for the most basic notions mentioned above, so we can consider the present question.

In particular it does not have radian measure - and we could imagine angle $S\!A$ as belonging to a set $\mathbb{A}$ which comprises all planar angles, ie right angles, acute angles, obtuse angles, reflex angles, and so on (ie as in Euclid's Elements, which does not use any angle measure). The geometric trig functions $\sin$ and $\cos$ would then be functions from $\mathbb{A} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$, and when an angle measure is introduced they would become functions $\mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$.

The well known analysis proof of convergence of $(p_{n})$ is made by formally defining radian measure of angle and by using the power series definitions of the trig functions $s(x)$ and $c(x)$. This requires a fair bit of work in analysis - for example the theory of differentiation, integration, and power series are all needed.

[The formal definition of radian measure can be made as follows :-

First of all let $f(x) = \sqrt{1 - x^{2}}$ for $x \in [-1, 1]$ (ie. the upper half of the unit circle).

Then define the improper integral $l(x) = \int_{x}^{1} \sqrt{1 + f'(t)^2} \:dt$ (= $\int_{x}^{1} 1 / \sqrt{1 - t^2} \:dt$) for $x \in [-1, 1]$ (ie from the formal analysis definition of curve length).

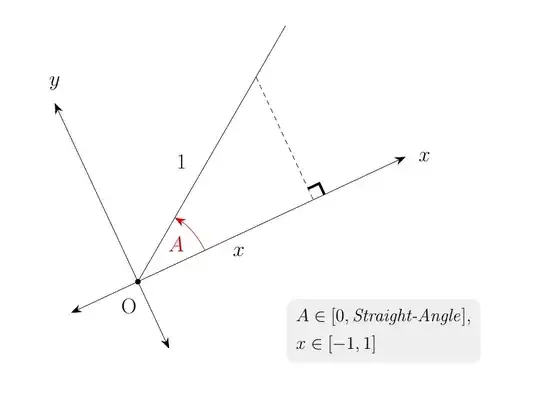

Then given $A \in [0, SA]$, where $SA$ denotes 'straight-angle', project a unit length of one of the sides of the angle perpendicularly down onto the other side and set up $xy$-axes as shown in the figure below. Then radian measure $m(A) := l(x)$, where $x$ = projection of this unit length onto the $x$-axis. For $A$ outside the range $[0, SA]$ we just add or subtract whole multiples of $m(SA)$ as appropriate.

Then we would have to prove :-

This function $m$ is a valid definition of an angle measure (ie it is 'additive').

$m(SA) = 2\gamma$, where $\gamma$ is the first positive root of the function $c(x)$.

Wrt this angle measure we have sin/cos from Geometry equal to the analytically defined s(x)/c(x) functions.]

Then with this formal definition of radian measure we could prove $(p_{n})$ converges to the real number $2\gamma$ as follows :- \begin{eqnarray*} p_{n} & = & n \sin \left(\frac{SA}{n} \right) \\ & = & n \, s \left( m \left(\frac{SA}{n} \right) \right) \mbox{(by equivalence of $sin$ and $s$ when using radian measure $m$)} \\ & = & n \, s \left( \frac{1}{n} \; m(SA) \right) \mbox{(by multiplicative property of any angle measure)} \\ & = & n \, s \left( \frac{2\gamma}{n} \right) \mbox{(radian measure of SA is $2\gamma$)} \\ & = & 2 \gamma \: \frac{ s(2\gamma/n) }{ (2\gamma/n) } \\ & \rightarrow & 2\gamma \:\: \mathrm{as} \:\: n \rightarrow \infty \end{eqnarray*}

since $\lim_{h \rightarrow 0} s(h)/h = 1$ from analysis.

This gives a rigorous proof of the existence of $\pi$, but note there is quite a lot of analysis behind that proof.

My question is is there some elementary geometric or algebraic method of proving $lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} (p_{n})$ exists (or equivalently it is a Cauchy sequence), which does NOT require this amount of analysis, but only needs the most basic definitions of limits of sequences and their elementary properties ?

One of the motivations in asking this question is that recently I came across a proof using only elementary geometric methods of the Basel Identity, $\sum_{n = 1}^{\infty} 1/n^{2} = \pi^2/6$, which formerly I understood as only been provable using fairly complicated or advanced methods, such as the Residue Theorem in Complex Analysis. It took some years for leading mathematicians of the 1700's to obtain a rigorous proof of this identity. This elementary proof is described in this YT video, and the heuristic argument described there can readily be turned into a fully rigorous geometric proof. (Although this elementary proof does make use of some basic real analysis, it does not require anything as advanced as the Residue Theorem).