I was trying to understand via a geometric argument why the projection (call it $p)$ of $b$ onto the line $a$ minimizes the norm of error vector $e = \| p - b \|^2_2$. i.e. I want to solve:

$$ \min_{x \in \mathbb R} { \| b - xa \|^2_{2} } $$

via a with a geometric argument.

Obviously this is very easy to solve with calculus because its a 1D calculus problem (take derivatives wrt to $x$ and set equal to zero to get $x=\frac{a^\top b}{a^\top a}$ ). However, it seems that from MIT's Gilbert Strang's 18.06 course, he keeps emphasizing that we want to choose $x$ s.t.

$$e \perp a$$

In other words it seems we should use orthogonality $ \langle e,a \rangle = \langle b-xa,a \rangle =0$ to solve the problem. This just seems to be a such a concise way of expressing the solution (only alluding to geometry via orthogonality) that it feels there must be some clean (elegant?) way to express the solution using only the orthogonality fact (or some other geometry trick maybe).

I started by expressing the error vector with dot/inner products and see where we might be able to insert the property that $e^\top a = (b-xa)^\top a =0$. So I proceeded:

$$ \| e\|^2_2 = \|b - xa \|^2_2 = (b-xa)^\top (b-xa) = (xa-b)^\top xa + (xa-b)^\top(-b) $$

I could have required $(xa-b)^\top xa = 0 $ to remove a whole term above but it wasn't obvious to me why that would be optimal.

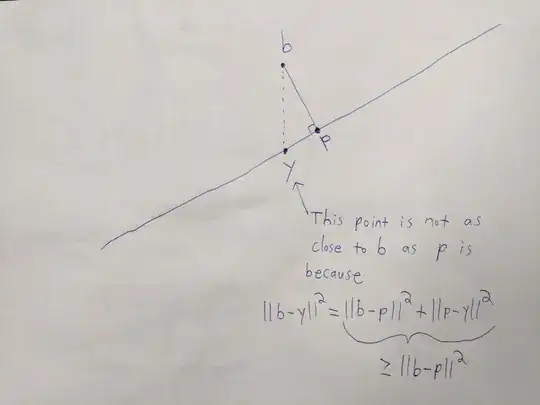

Somehow as I drew triangles and moved the error vector around it seemed to insist to choose the perpendicular vector which made me feel either (generalized) Pythagoras theorem or the law of cosines would be useful. Since the angle that has to be 90 is the one opposite to the vector $b$ (being projected) I used that vector as the reference for the law of cosines:

$$ \|b\|^2_2 = \|e\|^2_2 + \|xa\|^2_2 - 2 \langle xa, e \rangle$$ $$ \|b\|^2_2 = \|e\|^2_2 + \|xa\|^2_2 - 2 \| xa \|_2 \| e \|_2 \cos \theta(xa,e)$$

re-arranging terms to leave the error term $\|e\|^2_2$ as the subject leads to:

$$ \| e \|^2_2 = \|b\|^2_2 - \|xa\|^2_2 + 2 \langle xa,e \rangle $$

definitively setting $\langle xa,e \rangle = 0$ definitively helps the above term decrease (which seems in the right direction because $\langle a,e \rangle = 0 \implies \langle xa,e \rangle = 0$ since $e$ will be orthogonal to any multiple of $a$). However, it seems to me if we choose a different angle such that the $\cos \theta(p,e) = -1 $ or equivalently $\langle p,e \rangle = -1 $ that would lead to a greater decrease to the error vector than if we choose a perpendicular one. Which seem really unintuitive to me. Is the choice of -1 better? Though if I draw things by hand it seems clear that perpendicularity is optimum so it seems my maths by hand here is tricking me somehow...

Essentially right now it seems I got something (maybe) useful but I am unable to convince myself (or provide a rigorous proof) that the above is optimal. Furthermore it doesn't seem a super clean solution and was concerned that I was missing a very obvious/clear argument for why the optimal solution is $ a \perp e $ (also this seems like a standard textbook thing but I can't find a rigurous proof of it in Strang's book nor any of the other ones I have). What am I missing? There must be a better solution or at least a proof that this is right.

After reflecting on my question for a bit I think what I am really looking for is for a way to conclude that the pythagorean theorem sort of the "optimal" way to deduce the error side of the triangle is as short as it can be. It just feels there must be something that leads us from the law of cosines to the Pythagorean thm to your proof. Or something like that. It just seems maybe my question is more basic and shouldn't require vectors (or knowing about basis etc), just geometry (maybe how $\cos \theta = 0$ or $u^\top v =0$). Any more advanced knowledge of vectors should be unnecessary.

Note that the calculus solution is very simple:

The norm of the error vector $e$ is:

$$\|e\|^2_2 = (b - xa)^\top (b - xa) = b^\top b - 2xa^\top b + x^2a^\top a$$

To minimize $\|e\|^2_2$, we take its derivative with respect to $x$ and set it to zero: $$\frac{d}{dx}\|e\|^2_2 = -2a^\top b + 2xa^\top a = 0 \implies a^\top b = x a^\top a$$

Thus:

$$x = \frac{a^\top b}{a^\top a}$$

Note I did see:

but it doesn't provide the argument I am looking for...