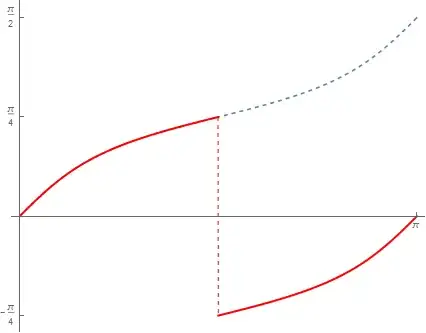

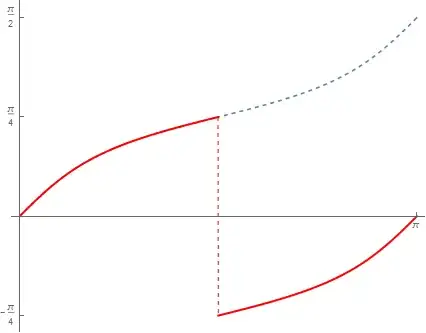

The issue becomes evident once we look into the graph of the actual antiderivative and the answer you found:

$\hspace{7em}$

The red line is your answer $x \mapsto \frac{1}{2}\arctan(2\tan x)$ while the gray dashed-line is the actual integral $x \mapsto \int_{0}^{x} d\theta/(1+3\sin^2\theta)$.

This discrepancy can be tracked down to the fact that your substitution $u = \tan\theta$ has discontinuity at $\theta = \pi/2$. In particular, $\tan\theta$ is not differentiable at $\theta = \pi/2$. Since the antiderivative technique is the reverse process of differentiation and differentiation fails at discontinuity, it is not surprising that anti-differentiation often fails at discontinuity.

There are some workarounds for this issue.

Reducing. One way is to manipulate your integral so that your substitution no longer suffers from this issue. Various symmetries can be exploited for this task. For instance, you can write

$$ \int_{0}^{\pi}\frac{d\theta}{1+3\sin^2\theta} = \int_{-\pi/2}^{\pi/2}\frac{d\theta}{1+3\sin^2\theta} = 2 \int_{0}^{\pi/2}\frac{d\theta}{1+3\sin^2\theta} $$

and apply the substitution $u = \tan\theta$ to any of the last 2 integrals.

Gluing. Although your substitution does not work on all of $[0, \pi]$, it does work on each subintervals $[0,\pi/2)$ and $(\pi/2, \pi]$. So your answer remains valid on each of these intervals. This suggests that

$$ \int_{0}^{x}\frac{d\theta}{1+3\sin^2\theta} = \begin{cases}

\frac{1}{2}\arctan(2\tan x) + C_1, & x \in [0, \frac{\pi}{2}) \\

\frac{1}{2}\arctan(2\tan x) + C_2, & x \in (\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi]

\end{cases} $$

Since the LHS is continuous on $[0,\pi]$, you can determine $C_1$ and $C_2$ so that the right-hand is also continuous at $x = \pi/2$.

\displaystylein titles. – Did Apr 12 '17 at 00:15