It is a fundamental problem, and there are some related problem asked before:

1. $\epsilon - \delta$ definition to prove that f is a continuous function.

2. How to show that $f(x)=x^2$ is continuous at $x=1$?

However, it seems I am confused about something.

In the definition by the textbook: Advanced Calculus, Folland p.14

The continuity of $f$ on $U$: For every positive number $\epsilon$ and every $a\in U$, there is a positive $\delta$ so that $$|f(x)-f(a)|<\epsilon \text{ whenever } |x-a|<\delta$$

or there is an equivalent definition:

show that for every $\epsilon >0$ there is $\delta >0$ such that if $0<|x-a|<\delta\,,$ then $|f(x)-f(a)|<\epsilon$.

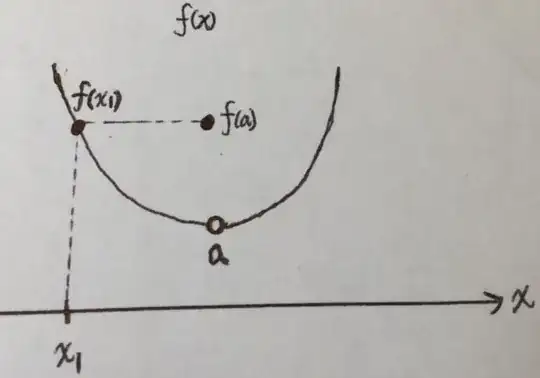

Now, apply this definition in the following picture. Obviously, $f(x)$ is not continuous at $x=a$.

Suppose the distance for the discontinuity gap is $D$.

If I want to use $\delta-\epsilon$ definition to prove this, should I say that:

$|x-a|<\delta$, where $\delta$ is very small; however, $|f(x)-f(a)|\rightarrow D$ at least. So it is not for all $\epsilon$.

Or should I say that:

$|f(x)-f(a)|\leq \epsilon$ where $\epsilon$ is very small; however, $|x-a|$ is about $|x_1-a|$ by the symmetry of the second order curve; which cannot be smaller anymore.

My question is:

Let $\epsilon = 0.00001 << D$; however, I can still find $x$ around $x_1$ such that there indeed exists $\delta = |x_1-a|$ such that $|f(x)-f(a)|\leq \epsilon$. So how do I define "small"? Which part I made mistakes?