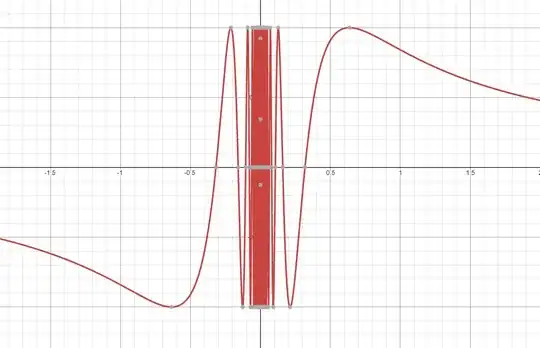

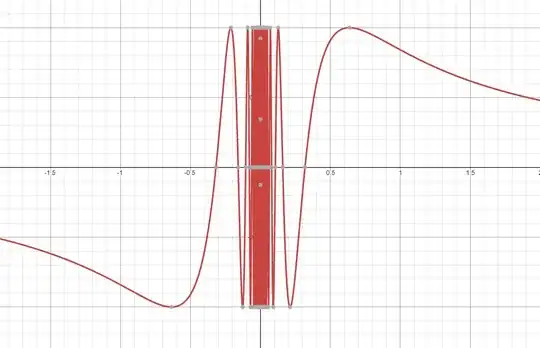

Lets look at $sin(\frac{1}{x}) $ function,

Now you can get a idea how it behaves near to 0. That is oscillating near 0. THat's why we can't get limit when x goes to 0 of $sin(\frac{1}{x}) $ function. So let's move into it's proof,

Have to prove $\lim_{x \to 0+} sin(\frac{1}{x})=Does \: not \: exist$

$$\forall \varepsilon >0 \; \exists \delta \; s.t \; 0< x < \delta \mapsto |sin\frac{1}{x}-L|<\varepsilon$$

Let $\varepsilon=\frac{1}{2}$,

$$0< x < \delta \mapsto |sin\frac{1}{x}-L|<\frac{1}{2}$$

Assume that, $$\lim_{x \to 0+} sin(\frac{1}{x})=L \; \in \mathbb{R}$$

Let $$x_{1}=\frac{1}{2n\pi+\frac{\pi}{2}} \; \; (n\in Z^{+})\; \; and \; \; x_{2}=\frac{1}{2n\pi+\frac{3\pi}{2} } \; \; (n\in Z^{+})$$

So we have to get range of n,

$$0<\frac{1}{2n\pi +\frac{3\pi}{2}} < \frac{1}{2n\pi+\frac{\pi}{2} }<\delta$$

$$\frac{1}{2n\pi+\frac{\pi}{2} }<\delta$$

So we get,

$$\frac{1}{2\pi\delta }-\frac{1}{4}<n\; \; (n\in Z^{+})$$

Now,

$$|sin(x_{1})-L|=|1-L|<\frac{1}{2}\Rightarrow \mathbf{C}$$

$$|sin(x_{2})-L|=|-1-L|=|1+L|<\frac{1}{2}\Rightarrow \mathbf{D}$$

By C + D we get,

$$|1-L|+|1+L|< 1$$

$$|(1-L)+(1+L)|\leq |1-L|+|1+L|< 1$$

$$2\leq |1-L|+|1+L|< 1$$

$$2<1 \; \;\; \; (\therefore contradiction)$$

Assumption is not true. $\: \: \therefore\:\lim_{x \to 0+} sin(\frac{1}{x})$ has no limit.