Homoousios - What does it mean?

This is a summary of my article on the meaning of the term homoousios.

In this summary, I removed all the quotations and provided only the conclusions to enable the reader may see the big picture. This is, in my view, a crucial subject that puts a new perspective on the entire fourth-century Arian Controversy.

These conclusions will seem heterodox to the average Christian but they're based entirely on the writings of recent world-class scholars. Over the last century, after ancient documents have become more readily available, scholars have realized that the traditional textbook account of the Arian Controversy is a complete travesty. For a discussion, see - The Revised Scholarly View.

The Nicene Creed was first formulated at the Council of Nicaea (AD 325). It says that the Son

- Was begotten of the substance (ousia) of the Father and that

- He is of the same substance (homoousios) as the Father.

‘Same substance’ has two possible meanings:

One Substance - In the traditional account of the Arian Controversy, the Trinity doctrine has existed right from the beginning. In the Trinity doctrine, God is one Being (ousia) but three Persons (hypostases). Therefore Trinitarians claim that the word homoousios in the Creed means that Father and Son are one single substance (one Being).

Two Substances – The alternative meaning is two substances (two Beings) with equal divinity.

But recent scholarship, however, seems to agree that homoousios does not have either of these two meanings. They say that it was intended to have a looser, more ambiguous sense.

Two Views at Nicaea

A minority was able to dominate the Nicene Council because they had the support of the emperor. Consequently, they were able to put the term homoousios in the Creed, despite the objections of the majority. So, we must distinguish between two meanings:

- The meaning the minority intended with the term and

- The meaning the majority assigned to it that enabled them to accept the Creed.

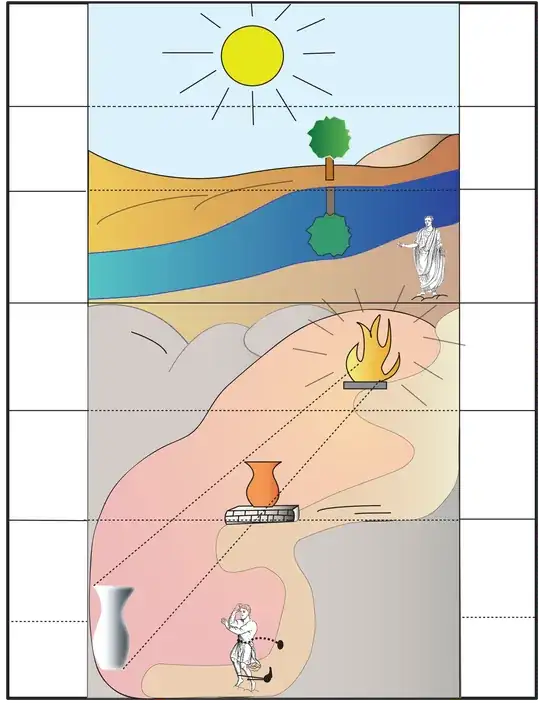

To determine those meanings, consider what homoousios meant (1) before, (2) during, and (3) after Nicaea:

In Greek Philosophy, Aristotle used the term οὐσία (ousia) to describe his philosophical concept of Primary Substances.

In Paganism, particularly in the theological language of Egyptian paganism, the word homoousios meant that the Nous-Father and the Logos-Son, who are two distinct beings, share the same perfection of the divine nature.

The Bible never talks about God’s ousia and never says that the Son is homoousios with the Father.

Gnostics used the term homoousios to indicate that the lower deities are of the ‘same ontological status’ or ‘of a similar kind’ as the highest deity from whom they were derived or emanated. But Gnostics were not really Christians and they did not use the term to describe the Son's relationship to the Father.

Tertullian (155-220), writing in Latin, nowhere uses any term corresponding to homoousios. He used “the expression unius substantiae.” In the past, it was often claimed that this is equivalent to homoousios but it means ‘mia hypostasis’ (one hypostasis).

Sabellius (fl. ca. 215) used the term homoousios in his theory in which the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are one and the same Person (hypostasis). In other words, he said there is only one substance.

Origen (c. 185 – c. 253) did not apply the word homoousios to the Son and did not teach that the Son is 'from the ousia' of the Father, despite claims in the past to the contrary. There is one celebrated fragment where Origen appears to sanction the use of homoousios, but the translator probably altered the text to make it appear consistent with Nicene theology.

Libyan Sabellians, around the year 260, described the Son as homoousios with the Father. They were meaning that the Father and Son are one single hypostasis (Person). Consequently, the Son does not have a real distinct existence.

Dionysius, bishop of Rome, agreed with the Libyan Sabellians that Father and Son were homoousios. He, effectively, was a Sabellian. His doctrine could only with difficulty be distinguished from that of Sabellius.

Dionysius, bishop of Alexandria, opposed those Libyan Sabellians and rejected the term because Sabellius used it in rejecting the distinction of hypostases. But those ‘Sabellians’ in Libya complained to the bishop of Rome who persuaded Dionysius of Alexandria to accept the term. However, the latter only adopted it with reluctance and only in a general sense, meaning ‘of similar kind'. In other words, for him, the term did not mean that Father and Son are one and the same or even that they are equal.

Paul of Samosata was deposed only a few years later in 268. Paul used the term to say that Father and Son were ‘a primitive undifferentiated unity’. That same council also condemned homoousion because it spelt to them Sabellianism.

Conclusion

Before Nicaea, the term homoousios was used only by Sabellians. They used it to say that Father and Son are one single Person. In their view, the Son has no real distinct existence. The only non-Sabellian to use the term was Dionysius of Alexandria, but he only adopted it with reluctance and only in a general sense, meaning 'of similar nature'.

Therefore, to determine the meaning of the term in the Nicene Creed, one needs to identify the theology of the party that was able to force the inclusion of the term in the Creed.

A Surprising Innovation

The inclusion of the term in the Nicene Creed must be regarded as a surprising innovation because it is not a Biblical term, was not part of the standard Christian language at the time, but was borrowed from the pagan philosophy of the day. Furthermore, the Sabellian history of the term rendered it particularly suspect. For these reasons, some very powerful force must have been at work to ensure its inclusion.

The Emperor’s Role

That powerful force was the emperor. In the fourth century, the general councils (the so-called ecumenical councils) were called and controlled by the emperors. They were the tools by which the Emperor ruled the church. In the Roman culture, the emperor had the final say in church doctrine.

Consistent with this principle, at Nicaea, the emperor not only proposed but also insisted the inclusion of the term. Constantine even dared to explain the meaning of the term.

Alexander's Party

However, Constantine did not come up with the term homoousios by himself. The term was favored by the minority party of Alexander. That party was able to dominate and insert the term in the Creed because the emperor took their side.

The leaders of that party were:

- Alexander himself,

- Ossius - the chairperson, as the emperor's representative, and

- the two leading Sabellians, Eustathius and Marcellus.

However, all four of them were Sabellians. The Nicene Creed, therefore, was the work of a Sabellian minority.

How was Homoousios understood?

How, then, did the delegates to the Council understand the term homoousios?

The Sabellians intended to term to mean that the Father and Son are one single Person (one hypostasis). Consequently, after Nicaea, the Sabellians claimed the Creed as support for their doctrine.

The majority, on the other hand, was able to agree to the Creed because they had accepted the emperor’s explanation that it simply means that the Son is truly from the Father. With that understanding, it does not mean that Father and Son are one Person or even that they are equal. However, after the council meeting, that same majority opposed the Creed because they thought it taught Sabellianism.

So, in conclusion, all parties understood the term homoousios in a Sabellian sense.

Post-Nicaea Correction

After Nicaea, the conflict over the term homoousios continued for a few years. I refer to it as the ‘Post-Nicaea Correction’ because it corrected the distortions caused at Nicaea by the sway of the emperor. This 'correction', therefore, should be regarded as part of the Nicene event.

By this time, Arius was out of the picture. Alexander also retired a year after Nicaea. The conflict was specifically between the Eusebian majority and the two leading Sabellians; Eustathius and Marcellus. As a result of this conflict, both of them were deposed for Sabellianism:

Not Mentioned

After the ‘Post-Nicaea correction’, Nicaea and homoousios were mentioned again for about 20 years. It was not regarded as useful or important.

During this period when homoousios was not mentioned, two councils were held that are important because they reveal the true views of the delegates at Nicaea.

East - At first, the ‘West’ was on the fringes of the Arian Controversy. For example, the delegates at Nicaea were drawn almost entirely from the East. So, what the delegates to Nicaea really believed when not compelled by the emperor can be seen in the Eastern Dedication Creed formulated in 431. It shows that they regarded the Nicene Creed as dangerously Sabellian.

West - Two years later, in 343, the West held a council at Sardica. The 'West' is generally known for being defenders of Nicaea, but the creed from that council explicitly says that Father and Son are one Person, which reveals the Sabellian preference of the West at this time. This is confirmed by their vindication of Marcellus, the main Sabellian at the time, in the year 431.

Neither of these councils used the term homoousios.

Athanasius re-invented Homoousios.

That would have been the end of homoousios. However, in the 350s – 30 years after Nicaea, Athanasius brought it back into the Controversy. Athanasius is known as the main defender of the Nicene Creed and homoousios during the years after Nicaea but, as another article shows, Athanasius also was a Sabellian. In his view, the Son is part of the Father. Athanasius, therefore, re-invented homoousios to defend his Sabellian theology; not to defend the Nicene Creed.

Anti-Sabellian Front

In the 350s, after homoousios had become a key factor in the Controversy, and the West attacked the East with it, the Eusebians (the so-called Arians) were divided into several factions with respect to homoousios, but they formed a united front against the Sabellian thrust of the Western church. This shows that the main enemy remained Sabellianism.

Meletian Schism

In the 360s and 370s, in what is known as the Meletian Schism, there were two factions in the pro-Nicene camp:

- The ‘one hypostasis’-side (the Sabellians) was led by bishop Damasus of Rome and by Athanasius.

- The ‘three hypostasis’-side was led by Basil of Caesarea. He regarded the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit to be three distinct Beings (substances) but he claimed that they have exactly the same type of substance. See – Basil.

Final Conclusions

Before Nicaea, the only Christian theologians who favored the term were Sabellians.

At Nicaea, a Sabellian minority was able to insert the term in the Creed, against the wishes of the majority, because the emperor took Alexander's part.

During the decade after Nicaea, the main drivers of the term homoousios were removed from their positions. There-after, the term was not mentioned again until Athanasius brought it back into the dispute about 30 years after Nicaea; not to defend the term as such, but to defend his own Sabellian theology.

The West accepted Athanasius’ explanation because the West was traditionally Sabellian.

Basil of Caesarea later accepted homoousios. However, he opposed Athanasius’ understanding of the term and explained it in a generic sense.

Therefore, before, during, and after Nicaea, the advocates of the term homoousios were Sabellians. It must be understood in a Sabellian sense.