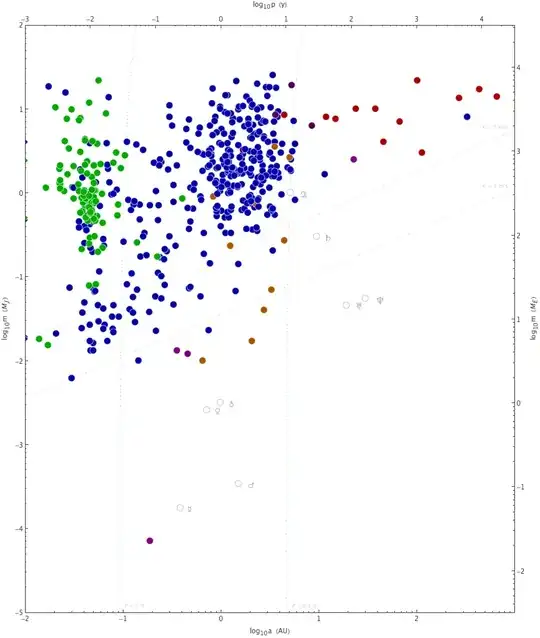

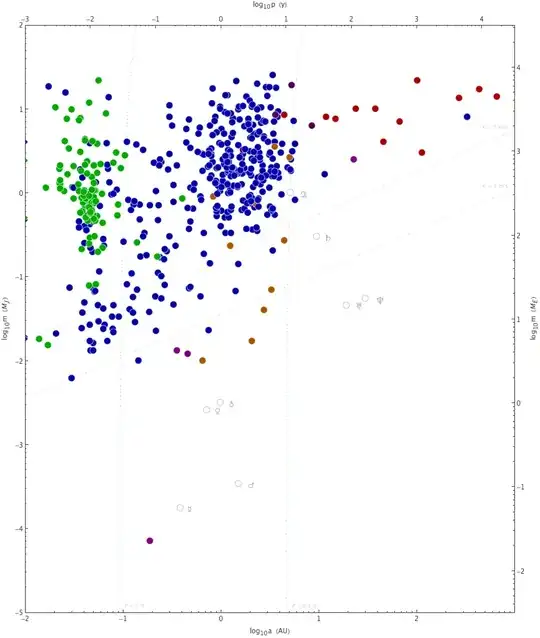

Because more massive, closely-orbiting planet exert much greater gravitational forces on their host star than smaller, more distant planets, there is a significant observational bias. We are much more likely to detect these planets (i.e. "hot Jupiters") because their observable effects (Doppler wobble, gravitational lensing, etc) are more significant.

The below image (from here) shows you that we're still mostly unable to detect planets like those in our own Solar system (the gray circles are our Solar planets). It's just too hard.

I don't study planetary formation (yet!), so I can't speak well for the theoretical side of things. All we've managed to collect so far is the very lowest-hanging fruit, so it is highly likely that there are is a large number of Earth-like planets out there too.

The authors of this article on the Kepler-10 system (you'll need MNRAS access) suggest planet-planet gravitational scattering or collision-merger events. The Scholarpedia article provides a bit more brief reading on these mechanisms. Here is a review article from 2009, and a more in-depth review from 2006.