Stars twinkle because their light has to squeeze through several different layers of the Earth's atmosphere. So why doesn't the moon twinkle as well?

-

4If you look at the moon through a telescope on a night when the stars are twinkling badly, you'll see the little craters wiggling about. That's wind in the atmosphere making them twinkle, just like the stars. Unmagnified, you can see it very well because every little twinkle is surrounded by bright lunar surface, not the blackness of space. – Wayfaring Stranger Mar 09 '16 at 15:40

-

In contrast to my answer, https://sites.google.com/site/fresnel4twinkle/ suggests that the phenomenon is poorly understood and the current popular explanation is incorrect – Danikov Mar 09 '16 at 16:49

-

1When I was first learning astronomy a sort of "rule" was told to me that "stars twinkle, planets (and other bodies) shine". So, if all the stars are twinkling but there is a red one that is not, that would be Mars. Granted, I've seen Saturn twinkle when the seeing is poor, so it's not always 100% right, but can be useful a fair amount of the time. – coblr Mar 09 '16 at 21:36

2 Answers

The first handful of hits on Google actually return incomplete and even wrong answers (e.g. "Because the Moon is much brighter" which is plain wrong, and "Because the Moon is closer" which is incomplete [see below]). So here's the answer:

As you mention, when light enters our atmosphere, it goes through several parcels of gas with varying density, temperature, pressure, and humidity. These differences make the refractive index of the parcels different, and since they move around (the scientific term for air moving around is "wind"), the light rays take slightly different paths through the atmosphere.

Stars are point sources

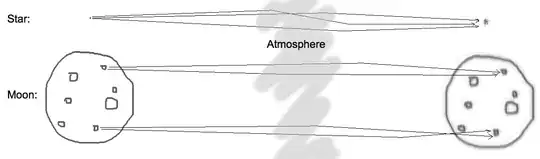

Stars are immensely far away, effectively making them point sources. When you look at a point source through the atmosphere, the different paths taken from one moment to another makes it "jump around" — i.e. it twinkles (or scintillates).

The region in which the point source jumps around spans an angle of the order of an arcsecond. If you take a picture of a star, then during the exposure time, the star has jumped around everywhere inside this region, and thus it's no longer a point, but a "disk".

…the Moon is not

The same is true for the Moon, but since the Moon (as seen from Earth) is much larger (roughly 2000 times larger, to be specific) than this "seeing disk" as it's called, you simply don't notice it. However, if you are observing details on the Moon through a telescope, then the seeing puts a limit on how fine details you can see.

The same is even true for planets. The planets you can see with the naked eye span from several arcsec up to almost an arcmin. Although they look like point sources (because the resolution of the human eye is roughly 1 arcmin), they aren't, and you will notice that they don't twinkle (unless they're near the horizon where their light goes through a thicker layer of atmosphere).

The image below may help understanding why you see the twinkling of a star, but not of the Moon (greatly exaggerated):

EDIT: Due to the comments below, I added the following paragraph:

Neither absolute size, nor distance is important in itself. Only the ratio is.

As described above, what makes a light source twinkle depends on its apparent size compared to the seeing $s$, i.e. its angular diameter $\delta$ defined by the ratio between its absolute diameter $d$ and its distance $D$ from Earth: $$ \delta = 2 \arctan \left( \frac{d}{2D} \right) \simeq \frac{d}{D}\,\,\,\mathrm{for\,small\,angles} $$

If $\delta \lesssim s$, the object twinkles. If it's larger, it doesn't.

Hence, saying that the Moon doesn't twinkle because it's close is an incomplete answer, since for instance a powerful laser 400 km from Earth — i.e. 1000 times closer than the Moon — would still twinkle because it's small. Or vice versa, the Moon would twinkle even at the distance it is, if it were just 2000 times smaller.

Finally, to achieve good images with a telescope you not only want to put it at a remote site (to avoid light pollution), but also — to minimize the seeing — at high altitudes (to have less air) and at particularly dry regions (to have less humidity). Alternatively you can just put it in space.

- 160

- 9

- 38,164

- 110

- 139

-

14"Because the moon is much closer" isn't strictly wrong — it doesn't get all that angular size by being bigger than stars. :) – hobbs Mar 09 '16 at 15:40

-

-

3

-

@hobbs: I was waiting for that one :) No, it's not wrong, but it's incomplete. A (powerful) laser 400 km above Earth's surface is 100 times closer than the Moon, and yet it would twinkle. – pela Mar 09 '16 at 19:29

-

1Wait, according to the third paragraph, planets should twinkle, since they are effectively point-sources. But then later you say they don't. Why not? – BlueRaja - Danny Pflughoeft Mar 09 '16 at 19:50

-

How did you get such a unique vantage point on your photo? And what filter did you use? #space – corsiKa Mar 09 '16 at 20:22

-

2@BlueRaja-DannyPflughoeft: Sorry, I see that it's badly phrased; all planets visible to the naked eye from Earth are not point sources, but many arcsec. But the resolution of the human eye is much worse than this, roughly 1 arcmin, I think. – pela Mar 09 '16 at 20:37

-

Don't forget that stars being billions of miles away will have a "considerable " amount of "matter" between us and them. "Matter" being gasses, dust and other things that might not yet be known, or are still theory. "Considerable" being > 0. – Spilt_Blood Mar 09 '16 at 23:49

-

1@Spilt_Blood: That matter can be completely neglected in terms of seeing. The light that we see from a distant star is the light that doesn't interact with gas/dust. Interacting means either being absorbed (in which case we just don't see it), og being scattered. But the probability of a photon being scattered exactly in our direction is infinitesimally small, so in effect it is also absorbed. Thus, the effect of interstellar matter is to reduce intensity, but not to make the star twinkle. – pela Mar 10 '16 at 00:56

-

@pela: but would that laser again have the size of the moon while beeing that close, it wouldnt be twinkling. probbably more it would extinguish humanity without a bit of noticeable twinkle ;P So propably its a relation of both variables together, making distance alone not correct anyway. – Zaibis Mar 10 '16 at 10:04

-

1@Zaibis: That's exactly my point: The distance isn't the important factor. The ratio between the real size and the distance of the object is. – pela Mar 10 '16 at 10:20

-

@pela: Maybe you should make this more clear. As thats not exactly what I extracted (while anyway I upvoted it allready ;) ) – Zaibis Mar 10 '16 at 10:22

-

@Zaibis: Thanks, I'll edit. I can see from the comments that you're not the only one who had this thought. – pela Mar 10 '16 at 11:18

-

Does the twinkling really have to do with human eyesight? Isn't it about photons getting scattered by hitting air molecules? Betelgeuse is one of the few stars the surface of which can be resolved in big telescopes. I suppose that its rate of twinkling (and it twinkles less than other stars, doesn't it?) has to do with its apparent (tiny) angular size relative to the distances between or sizes of the molecules in Earth's atmosphere. – LocalFluff Mar 10 '16 at 14:31

-

@LocalFluff: No, you're right, twinkling doesn't depend on the resolution of the eye. I just meant that, twinkling aside, your eye can't resolve the disk of a planet (save perhaps Venus at opposition), so a point source of the same brightness would look the same if it weren't for the twinkling. – pela Mar 11 '16 at 10:58

-

1@pela this is not "scintillation". Scintillation is moment to moment variation in amplitude of a light beam, not moment to moment variation in position. – it's a hire car baby Jun 26 '16 at 16:10

-

The wikipedia page on twinkling, aka scintillation, covers it quite succinctly; it boils down to the fact that distant stars are sufficiently distant to be a point source of coherent light. Solar planets and Luna are close enough to have a resolvable diameter while being visible, which means that their light is not coherent like a point source's might be.

Mathematically, the threshold at which a distant source of light becomes an effective point source is going to be a function of its size and distance, relative to the aperture size of the viewing device (in this case, the human eye). You could effectively think of it as a cylinder between the aperture and the perimeter of the light source: when that cylinder is sufficiently narrow when passing through the atmosphere, you get visible twinkling.

It's important to note that scintillation is not the mirage effect, which is caused by temperature gradients in the atmosphere and causes the 'swimming' effect. Scintillation does not displace the apparent position of the light source, instead resulting in variations of brightness and colour. The actual mechanism of scintillation results from plane-wave light and atmospheric turbulence causing interference in that light's wavefront. This is clearly demonstrated by this image from NASA.

- 171

- 2

-

Do you have a reference for the claim that scintillation is a wave interference effect rather than simply a geometric-optical one? – Ruslan Aug 01 '23 at 19:22