First of all: Science is not a democracy. The majority/mainstream is not always right, the minority (or even an individual) not always wrong (case in point: Dan Schechtman).

Now, having an "exotic" opinion does not make it right. Hence, one principle which I found useful to apply when considering an exotic opinion is whether it is a genuine opinion of whoever expresses it. I distinguish this from just parroting someone else's opinion - examples for the latter are conspiracy theories; furthermore, there are other expressions of opinions, such as conjuring of structure, or rhetorics.

Genuine Opinion

If the opinion is genuine, you can learn from it. You do not have to agree, but I found it fun to learn from this. In fact, I had some of my most enjoyable discussions with people like that and in several cases managed to turn their own thought complex around and convince them why the scientific method is actually the right thing to do - it worked because their thought complex was genuine, and expressed an - even if unorthodox - intellectual honesty. People like that can be brought to appreciate (even if not always agree) with "classical" science. On the other hand, they can be very inspiring discussion partners from which one can learn alternative (even if possibly incorrect) perceptions on the world. One needs patience - and only spend that time if you like that type of discussion, but it can be rewarding.

Reproduced Opinions

Then there are the others: the ones who reproduce scientific conspiracy theories. These people are not interested in science or an approximation of "truth". Rather, this is - in my experience - driven by contrarianism to the "scientific elite", distrust of scientists due to regular reports on scandals, the inherent doubt of science, or political agendas (about these more below). This cannot be addressed by purely scientific means, although you will need to know your facts extremely well. However, much more important is to address the agenda that these people have or inner contradictions. It can help to operate with their own thinking.

I'll invent a synthetic example: say, somebody believes the moon landing was faked. There are of course a lot of down-to-earth arguments trying to establish why this belief is wrong. However, a true believer may not be swayed by them. Rather, here one could address the question of whether they believed that humans built the pyramids. If they say yes, then the question would be why they believe that 4000 years ago people were able to build pyramids and in the time of rocket, atom and transistor they should not be able to send a human to the moon, when satellite communication is almost standard. If they say no, e.g., they were helped by aliens in building the pyramids, then one could play the ironic game and ask why they think those aliens couldn't have helped NASA, after all they can always consult them in Area 51 - make sure you wear a smirk to avoid being mistaken for taking this belief serious, of course. The point is not to convince them, but play a "Xanatos Gambit" where they have a choice of going for the boring down-to-earth explanation that conventional people accept, or pushing their own far-fetched belief to absurd conclusions. This method works surprisingly often when appropriately used. It corresponds to a proof by contradiction in math.

Conjuration of Structure

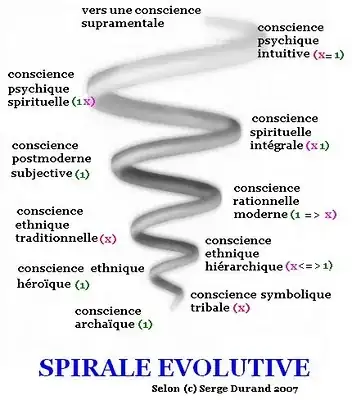

The example OP shows probably falls into this category - self-enamoured conjuration of structure; it is trying to bring order into a chaotic field. It recalls the way alchemists tried to structure the world, or, to name a more concrete example, Keplerian's Harmonices Mundi. While there is no real evidence to it, it is a mental exercise - sometimes to be taken more, sometimes less serious - to put things into their rightful place.

It fails to deliver scientifically because it has no predictive (and often no really postdictive or even descriptive) power. Sometimes, such as in Kepler's case, it was a serious attempt. Many mystical/kabbalistical practices have a significant element of conjuring symmetry or proto-mathematical structures, but in other cases, the structuring may well be purely verbal (as in OP's case).

The most ironic thing is that the theory modern elementary particle physics (think: the "Eight-Fold Way") ended up looking (superficially) quite similar to those mystical diagrams; of course, there is much more mathematical structure below the surface to make it work, but it seems that the need for patterns is very strong in humans.

If you have a conversation like that, one way to productively handle it can be to ask/discuss why the structure was chosen the particular way it is presented and not differently. If a serious attempt to explain is undertaken, the conversation can be productive. Otherwise, treat them like the guy that monopolises the piano at a party to tinkle some tunes: enjoy it or leave it. In that case, they may not have found truth, but perhaps a glimpse of beauty, at least for themselves.

Rhetorics

This group of people is interested in being right. Not making a scientific argument, not approaching the truth, not beauty, not even propagating a political agenda, but being right. Unless you like eristics, in which case, you should study the relevant methods and their defences (check e.g. Schopenhauer for this), this is not a good investment of one's time.

Bonus point: Political Agendas

Whenever science is not anymore about pure facts or operational successes (making a radio or airplane fly), but has an effect on society (point in case: "climate change"), science is prone to become a tool in the political argument. Here agendas are imposed on the facts one focuses on (a form of "consciousness forms the being"). Since in societal dynamics there are strong agendas, and since the feedback for outcomes of actions can be delayed by decades, it is not easy to link scientific claims about the future to current action. Furthermore, over such intervals, even scientifically honest predictions can be significantly wrong.

In this case, it is wise to understand one's own limitations in understanding and deciphering the world around us and try - in a Socratic manner - to discuss with one's peers the potential routes of what might actually be happening. In such complex systems, no-one is in possession of the full truth and getting the process right is here probably more valuable than trying to tell somebody that they are wrong. In this context, it is more productive and one gets better results if one can move the discussion away from the emotional dimension - this is sometimes hard, but it is the best way of making the conversation productive.

Note that this means also being less self-confident about what constitutes the politically appropriate process to shape the future. People, even people disagreeing with us, think a particular way for a reason - and that reason is what needs to be taken into account in a political argument and reconciled with the reality which is the same for all of us and does not depend on our particular opinion. One does not have to agree with the reason, but one must understand it if one wishes to communicate.